Managing Product Design Teams

Karl Neubacher’s work exposes the absurd and dangerous sides of compulsive conformity to norms.

For the past few years, I’ve been writing and speaking extensively about the failures of product design. Too often, talented teams are pulled off course by processes operating under the guise of “best practices” that slow down everything and produce mediocre outcomes.

While there is no universal system that can magically fix these problems, I believe there are foundational principles that the best design and engineering teams rely on to create meaningful products. We have followed these ideas at Design Systems International since day one. In this post I want to share some of these principles, inspired by a talk I gave at MongoDB in 2024, in the hope that they can be useful to others facing similar challenges.

The trouble with best practices

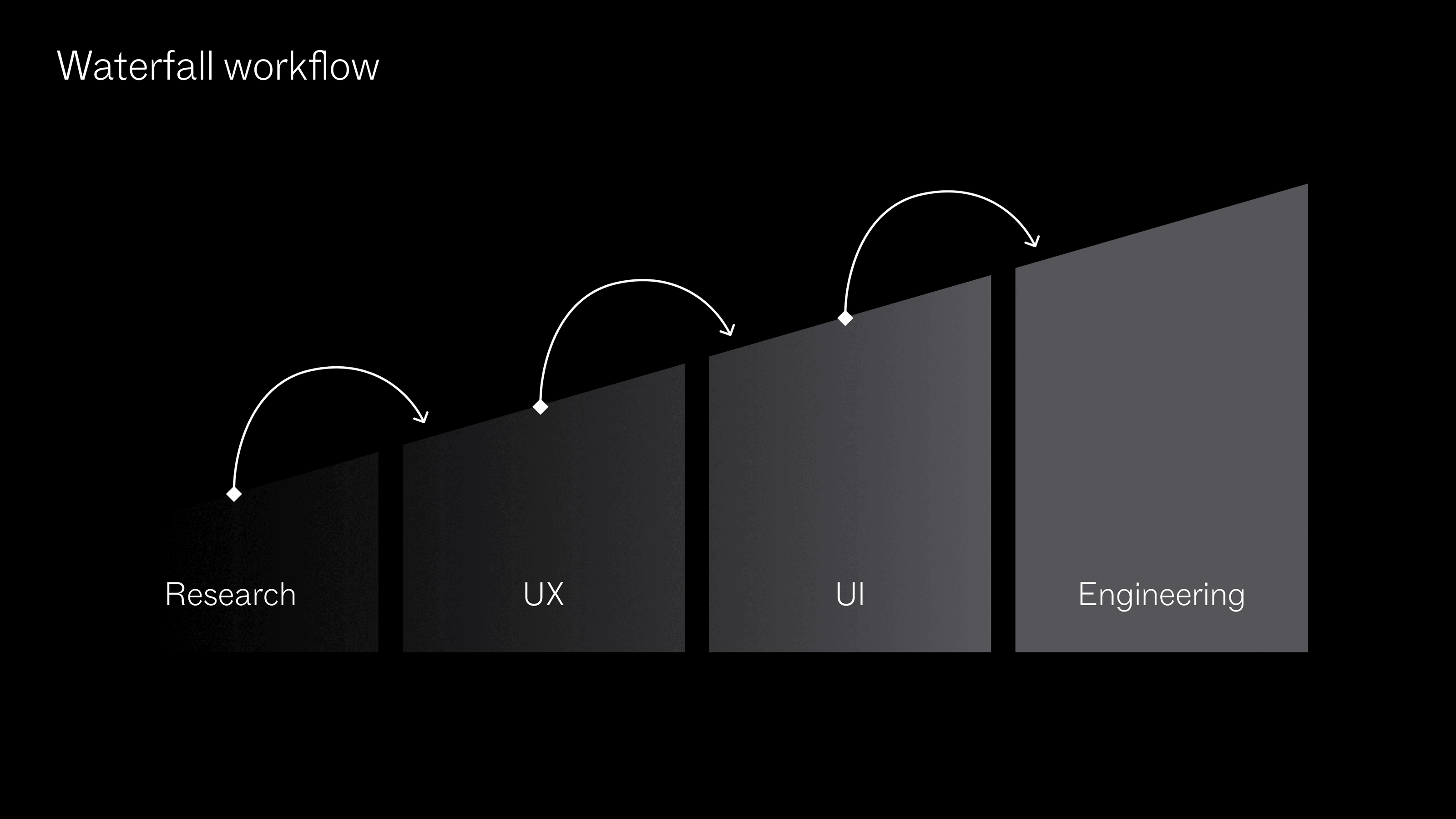

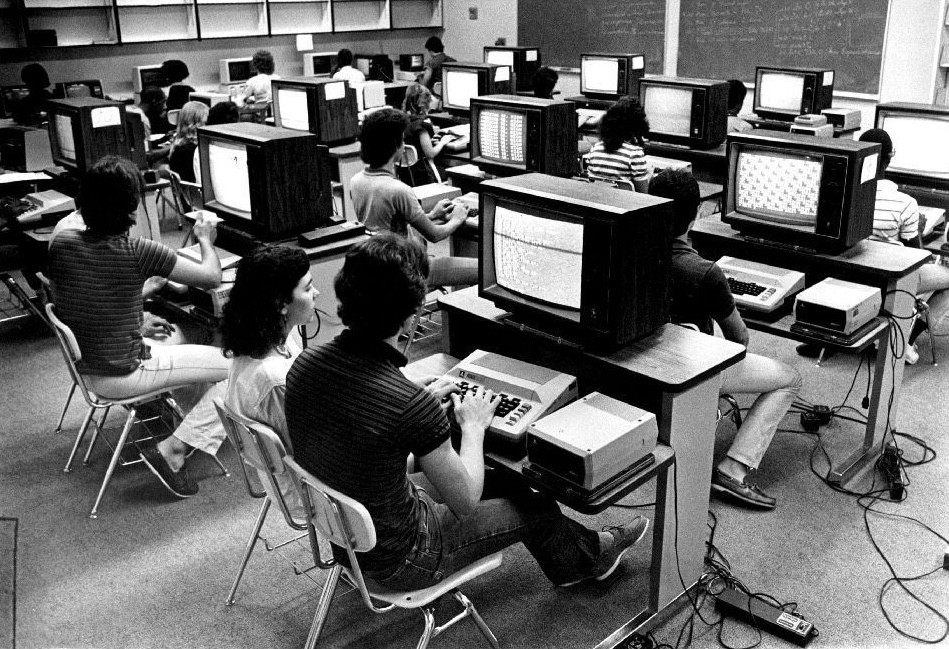

In many product design teams today, work is divided neatly into fields. Each field has its own tools, and over time, those tools have come to define the boundaries of the work itself. The result is a familiar waterfall process, where strategy leads to UX, UX leads to UI, UI leads to “finished” designs, and only then does engineering begin.

A traditional waterfall process with handovers between each stage

Most of the team’s energy goes into producing artifacts for this flow. Storyboards, user journeys, and wireframes are all methods that once helped keep design human-centered, but are now implemented as key deliverables needed for businesses to measure progress. Some businesses, uncomfortable with the uncertainty traditionally associated with the design process, have forced design to operate entirely in these predictable stages. Others have implemented strategies to be more integrated, yet the conflation of tools with roles is ever present. Many companies manage to design and build great products in these siloes, but might not realize the costs involved.

One cost is that the work is slow. Product teams struggle under the weight of these processes and, at worst, end up filling their time completing checklists instead of doing impactful work. Because the work is done in isolation in page-based, manual design tools far away from the medium we’re designing for, the outputs tend to be derivative, perpetuating a pervasive monoculture in digital design. On top of that, these processes come with a strong bias towards objectivity, often reducing design to an act of averaging user opinions, which further promotes monoculture. And perhaps most damaging, the waterfall process enables a design process that is entirely detached from the technology we’re designing for. The usual response to these issues is more process and more managers, which lowers productivity even further. The real solution is to break out of these rigid practices altogether.

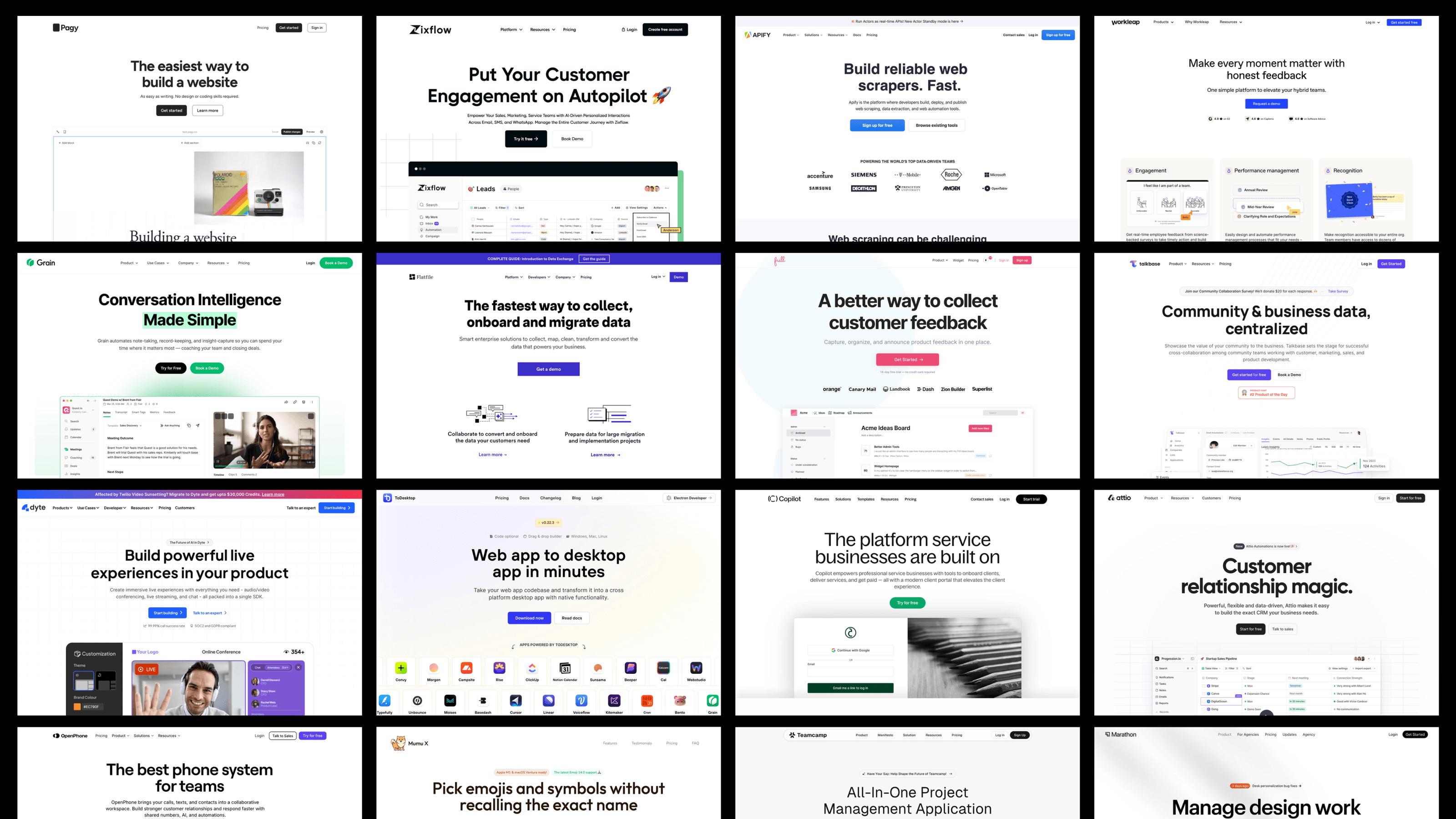

There's a fine line between relevant user patterns and design monoculture

Digital media is one of the most exciting places to design because it’s dynamic and interactive. I believe that designers can bring immense value to the production of digital products, yet our practices too often fail to deliver on that promise. We are eroding the speed, the quality, and the creativity that make design valuable in the first place.

A new set of principles

Watching these patterns unfold raises bigger questions: why can’t many large product design teams work together more effectively, move faster, and still deliver quality at scale? We have explored these questions with our own team in projects of all sizes, and along the way identified a set of guiding principles. What follows is that list, organized into three themes that build on one another to form a pyramid of needs for product teams.

Position design for organizational impact

In order to get to some of the more interesting ideas, organizations must first create the basic structures that give teams a better chance of success. These are the three most important principles to create that foundation:

-

Create interdisciplinary teams focused on specific areas of your product. This lays the foundation for all the other principles by placing researchers, designers, and engineers inside a single unit. It enables teams to move beyond the waterfall, applying both design and engineering as methods throughout the process of making a digital product. The result is deeper collaboration and a stronger sense of shared ownership over the final features.

-

Support teams through advisory. With interdisciplinary teams, design and engineering leaders need to focus on maintaining alignment across teams. One effective way to do this is by acting as cross-team advisors. In this role, leaders guide and support without becoming bottlenecks, creating self-managing teams that take ownership of their work and collaborate directly with other teams without going through several layers of management. This creates a truly agile organization where everyone is measured against the goals of the organization rather than the priorities of a single manager or department.

-

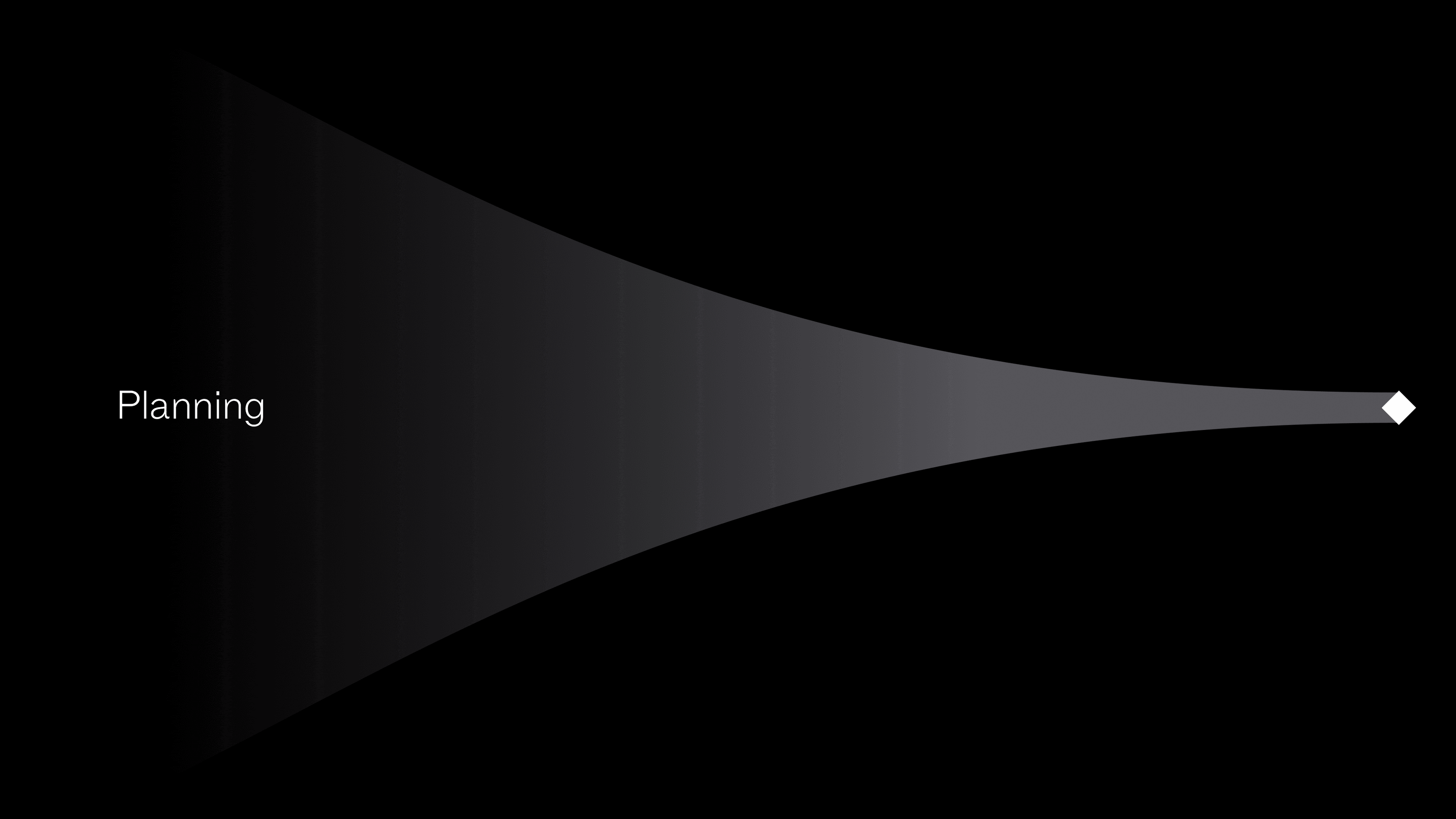

Plan like a farmer by being deliberate about planning. A farmer has a clear goal (grow the best apple), but knows it is impossible to predict the weather. Instead of laying out a rigid plan ahead of time, they stay agile and respond as things happen. Product teams should adopt a similar approach and avoid rigid planning strategies. This means less upfront estimation, deliberately choosing to either have a fixed timeline or fixed features but not both, and embracing the fact that plans can and should change as new findings emerge. This makes design more impactful, since designers are great at embracing uncertainty and perform well within it. While organizations may feel uneasy with that early ambiguity, giving designers and engineers the ability to adjust course based on early findings, can save a lot of time and money down the road.

Speed up the pace of production

Once the basic organizational structures are in place, a goal for any product design team should be to deliver quality results faster. These principles help shape the product design process around interdisciplinary collaboration.

-

Make code the design product by deliberately removing formal design deliverables. Users will never see a Figma design of the product, so designers should focus their attention on the product itself, rather than these intermediate artifacts. Designs may start in a design tool, but they should quickly start moving freely from design files to code and back, with a tight collaboration between designers and engineers until the product is ready to ship. While this approach benefits any design process, there are many features, such as data visualizations or complex design systems, that simply cannot be designed entirely in Figma. Recognizing this and gaining a more agile workflow with less blame between design and engineering helps product teams work smarter, because the process encourages deeper collaboration across disciplines. An added benefit is that it frees teams from the limitations of static, page-based thinking and enables more dynamic, product-first design ideas

-

Embrace a prototyping mindset might sound like pulling design into engineering, but a better analogy is that it invites engineering into the design process. Developers traditionally operate in environments with little room for mistakes, which is why we lean so heavily on elaborate design specifications. This is also why businesses often believe that design is cheap and engineering is expensive. By removing the rigid specification, engineering can become a powerful force in shaping design directions. Teams can design features that are grounded in technical feasibility, build and test prototypes much faster, and make mistakes at a point where the financial implications are low. Just as important, this approach fosters deeper collaboration, breaking down the old divide where design hands off and engineering takes the blame.

-

Measure outcomes, not process. Slow pace is often a consequence of an excess of processes that were intended to keep teams on track. We should remind ourselves that the map is not the territory and be careful about mixing up the concepts of doing work and tracking work. Although a collection of tickets to describe new functionality might be useful, they are not the actual functionality. Teams should orient themselves around making real things and judging their progress by what has been shipped. A big step in the right direction is changing the focus of meetings, giving priority to conversations that revolve around real artifacts such as shareable preview links or short demo videos as opposed to abstract ideas or plans. This anchors feedback in what exists, and it’s an excellent way to filter out conversations that may never move beyond planning.

Pull engineering into the design process

Unlock the full potential of design

One of the most damning things about current product design practices is that the resulting work is just bland. It chases after the latest trends and gets stuck in habits that are already oversaturated. This final set of principles creates a framework for bringing new thinking into the digital design process.

-

Stop the tool dogmatism. One of the greatest strengths of designers is our ability to work within ambiguity. The best designers I know can move fluidly between tools, early and often. They might prototype something in code, sketch an animation in After Effects, or draw an idea on pencil and paper. This principle enables interdisciplinary teams to work on whichever problem is the most pressing, in whatever tool is the most applicable. This also includes designers working in code. I don’t believe that all designers should be fluent in code, but they should be curious towards technology as it opens up interesting possibilities. An added benefit is that it tends to eliminate bad decisions by lowering the chance that designs will have major technical repercussions down the line. It also removes the need to build pixel-perfect, interactive prototypes only to start again from scratch in code. Furthermore, it’s an excellent way to narrow the gulf between design and engineering that both slows down the product timeline and makes it harder to create great digital products.

-

Encourage code-based experimentation. The design of a digital product is not only what it looks like but how it feels, and code should be treated as a material for designers just as paint is for artists or wood is for carpenters. Most of the current design tools keep us far from that medium, which tends to slow down the work and limit ideas. Elements like loading states, error handling, interactions, and animations shape the feel of a product as much as the visual design, and these things can only really be explored in code. To create work that feels distinct and valuable, teams should bring engineers into the process early and experiment directly in code, whether it is to shape product features or to influence a brand identity. As the boundaries between brand and product blur, technical expertise has become essential and is a powerful force for creativity. Our team has used this principle to design a logo as a program, a visual identity as a 3D mesh, and a visual language built on object recognition models, and many of these ideas bleed directly into the product.

-

Invest in custom design tools. Great design often deteriorates when applied at scale. A product may look great on release, but over time incremental changes lead to broken layouts, creating design debt that is notoriously hard to keep up with. One way to sustain high quality over time is to study how people work and improve their tools and processes. Traditional design tools don’t account for the rules and processes of your organization, so quality and consistency have to be enforced culturally, which is a task that increases exponentially in difficulty as teams grow. Custom design tools can be any piece of software that encodes and executes the design rules of your organization, allowing designers to create assets based on your unique rules and systems. This can be anything from a web-based illustration generator to a Figma plugin to generate components from a set of design tokens. It’s rare that we deliver any brand or product work without a custom design tool. While this approach requires a bit more upfront work, the payoff is significant in the long run. It allows designers to quickly experiment with options without having to worry about complex brand rules, leaving space to explore their own creativity. Project-specific tools absorb complexity, freeing teams to focus on what matters.

These principles won’t magically solve every problem in product development, but I do believe they offer a foundation for building better digital products. We’ve seen them work in many organizations of different sizes, especially when introduced in small steps and then scaled.

While writing this, two books have been especially influential: Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux and Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective by Kenneth O. Stanley. I’ll close with a few lines from the latter.

The idea that all our pursuits can be distilled into neatly-defined objectives and then almost mechanically pursued offers a kind of comfort against the harsh unpredictability of life. [...] To arrive somewhere remarkable we must be willing to hold many paths open without knowing where they might lead.

Objectives are well and good when they are sufficiently modest, but things get a lot more complicated when they’re more ambitious. In fact, objectives actually become obstacles towards more exciting achievements, like those involving discovery, creativity, invention, or innovation.